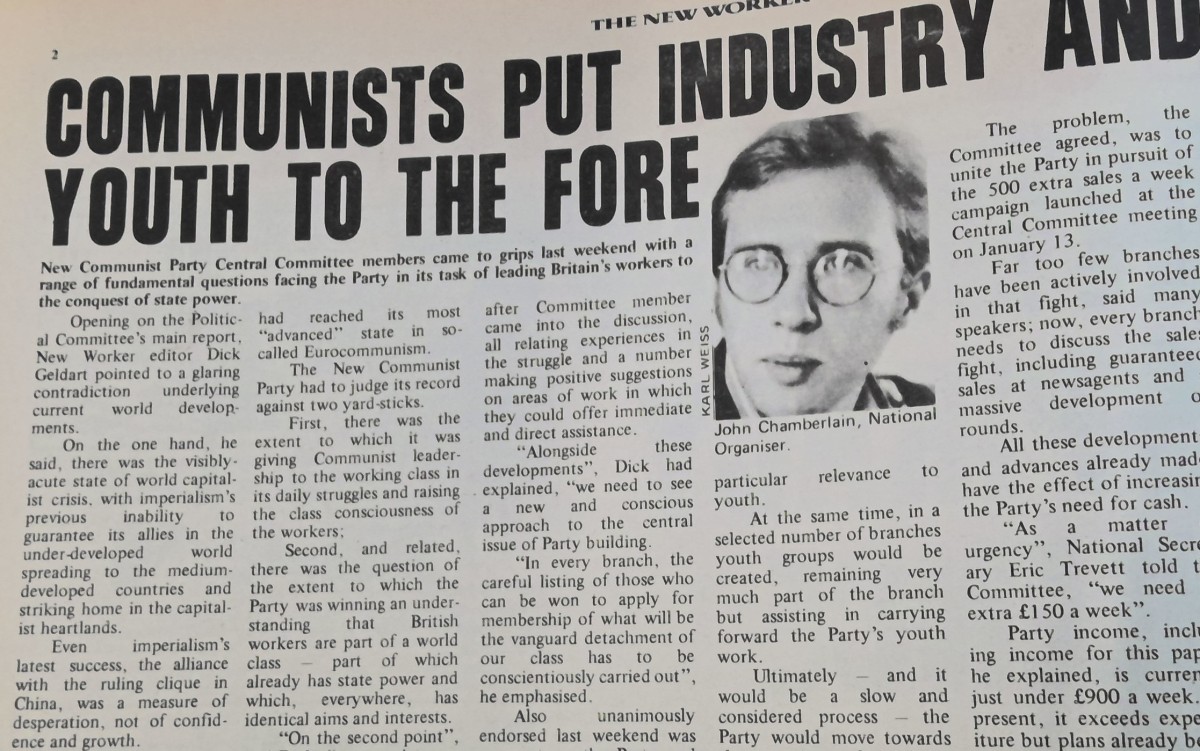

We reproduce here a July 1979 article from the New Communist Party’s (NCP’s) New Worker newspaper by John Chamberlain, who was one of the founders of The Leninist faction that re-entered the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) in the early 1980s. Chamberlain had been made national organiser of the NCP in March 1979, although he was removed in December 1979 and expelled in November 1980 after he and his supporters had come under the influence of the Communist Party of Turkey/Işçinin Sesi (Workers’ Voice) faction. To the best of my knowledge, it hasn’t been published on the internet previously.[i]

Of course, I’m sure the comrade might not completely welcome its republication given that some of it is standard NCP fare of those years and a quack diagnosis of the problems facing the world communist movement (an analysis inherited from the NCP’s founder, Sid French). ‘Proletarian internationalism’ is equated with support for whatever the Soviet Union was doing and is the proposed cure for the opportunist ailments afflicting the CPGB. Factions and factionalism are seen to be tools of the social-democratic right in communist organisations (despite this being the view of Sid French’s faction). And a struggle against 1979’s revisionism is premised upon the re-establishment of yesterday’s revisionism in the shape of Harry Pollitt’s CPGB of the 1940s and 1950s. So, there is nonsense aplenty here, although the strange notion of the “Soviet Trotskyite Bukharin” is one refreshingly innovative take on history.

Nevertheless, the article is interesting in that it illustrates how quickly the four comrades who founded The Leninist then developed their ideas under Turkish guidance. Remember, the first issue of this latter journal only appeared in 1981 and nearly all of the NCP’s assorted dogmas had disappeared by this point. I’m aware that comrade Chamberlain is now partially embarrassed at early issues of The Leninist but when put in the context of crude articles such as the one below, a different perspective arises. If The Leninist was a ‘warts-and-all’ product of the CPGB’s post-war left opposition, those warts had rapidly diminished in size from a few years earlier.

A careful reading of the article also shows that comrade Chamberlain’s gaze was not solely on the NCP. Despite the valedictory headline and surface denunciations, here is a young activist who was prepared to partially admit the NCP’s problems both in relating to comrades left behind in the CPGB and gaining recognition from the Soviet Union (a fool’s hope for the NCP if ever there was one). Also, Chamberlain’s gaze is on the CPGB and assessing the struggle inside that organisation and its failing Young Communist League. After all, why bother to go into such detail about the CPGB if you didn’t fundamentally care about it? In reality, it wasn’t too much of a jump from analysing the inner machinations of the CPGB (and later producing a review article on the CPGB’s Marxism Today in August 1979[ii]) to pitching up a faction inside it and calling for pro-party comrades to join in the cause of facing down liquidationism.

[i] https://communistpartyofgreatbritainhistory.wordpress.com/2023/01/01/new-communist-party-1977-80/

[ii] J Chamberlain ‘Revisionism Today!’ New Worker 31 August 1979.

John Chamberlain ‘After two years… history has absolved us’ New Worker 29 July 1979

The New Communist Party had its second birthday last Monday. It has had its problems, but nothing like those of the ‘official’ communists we left behind.

Today, the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) is engaged in a bitter internal struggle with the battle lines being drawn for its forthcoming national congress.

Just this week, the executive committee of the CPGB was forced to admit a 20 per cent drop in claimed membership, though avoiding any serious estimate of its causes.

In fact, and significantly for the future, the main reasons given added up to a catechism of complaints about existing socialism. Hoary old tales about ‘dissidents’ and even an outrageous allegation that China and Vietnam are both ‘socialist countries’, though at war, came into the CPGB’s list of excuses.

It might be reasonable to suppose that, with the working class facing an onslaught from the Tories and with the British capitalist system plunging into a new economic crisis, the CPGB would be engaging in a serious debate on the best way to overthrow the Tories and construct a strategy to lead the working class to the conquest of state power.

If you did suppose that, you would be very wrong. In fact the party is consumed in a debate over inner-party procedure.

There would, of course, be nothing wrong with such a debate if its purpose was to build a party with an organisational structure suited to the overthrow of capitalism. In fact, however, the debate is over whether to discard the last vestiges of communist organisational principle.

At the heart of this furnace of irrelevant chatter is a hefty document, the ‘Report on Inner-Party Democracy’. Its weight arises, at least partly, from the fact that it contains both a majority and a minority report.

The minority report appears under the signature of six members of the reporting commission, most notably the CPGB national organiser Dave Cook. It calls, in essence, for the permitting of factions in the party during the pre-congress period.

‘Factions’ is not, it seems a useable word – yet – and is studiously avoided but, call them what you will, they smell the same.

‘Organisations’, says the minority report, should be allowed to be established, uniting party members with similar views and with the authority to call private and public meetings to put those views forward. These ‘organisations’ would be permitted to publish their own documents.

The CPGB is, as is well known throughout the ‘left’, already riddled with factions, tolerated by the party leadership in a desperate effort to preserve the appearance of unity. Cook’s proposals would mean throwing away this pretence and ceasing to make any claim that the CPGB is a disciplined Leninist party.

Cook further proposes that the party abandon the recommended list election system for party congresses. Similar proposals have come from the revisionist right in the CPGB on several previous occasions.

This time, adoption of the proposal would inevitably leave Cook and his allies in a stronger position within the party and would lead to a further reduction in the proportion of working-class representation within the party leadership.

‘Hardcore’ social-democratic elements within the party would also get a boost from adoption of Cook’s plans to open up party advisory committees (committees of party members in particular spheres of work) to people from outside the party’s ranks.

Added to this change in the composition of the committees would be a change in their powers. The word ‘advisory’ would, in fact cease to have any meaning as they would be permitted to decide policy rather than merely to make recommendations to the leadership.

In short, the power of the leadership would be circumvented and the party’s democratic procedures turned into a charade with decision-making placed in the hands of elements not even formally in the organisation.

When the New Communist Party was formed in 1977 we pointed out that the CPGB would inevitably move to the right at an accelerating pace.

We added that, in conditions of developing crisis, unprecedented attacks would be made on the living standards of the working class, attacks dictated by the need of the capitalists to restore profit ratios.

In these circumstances, we concluded it was vital to the entire working-class movement that there should be a party committed to Marxism-Leninism. We proceeded to found one.

Some of our old comrades did not agree with us at that time, and, even though our basic propositions have each been proven, some continue to disagree…

The struggle against the right in the CPGB is not a new phenomenon. As far back as 1965, Sid French, the man who was to become the national secretary of the NCP, was warning the party membership of the growing revisionism within the CPGB.

The struggle intensified in 1966 over the question of abandoning the historic Daily Worker and launching the allegedly ‘broader’ Morning Star. From then on the merry-go-round whirled ever faster.

The more the party abandoned Marxism, the fewer workers there were in the party, the more remote the party leadership became from the realities of class struggle, the more irrelevant their positions became to the task of revolution.

Inch by inch their obsession with ingratiating themselves with ‘liberal’ opinion grew, until, ultimately, it became a monster. From small differences with the mainstream of world communist opinion they moved to alliance with the chorus of abuse against the Soviet Union and other socialist countries.

They attacked the 1968 defence of Czechoslovak socialism, denounced aspects of working-class power in the socialist world as undemocratic and began to praise ‘dissidents’ as clarions of freedom.

Today, even the man who formally leads the opposition to Cook over the ‘Inner-Party Democracy’ proposals is a person who has previously called for the rehabilitation of the convicted Soviet Trotskyite Bukharin. So much for the prospects of a ‘centre-left’ alliance!

These developments have been mirrored in the party’s youth organisation, the Young Communist League, but the youth have gone far further, far faster.

As long ago as 1968, YCL general secretary Tom Bell had the sheer cheek to call for an ‘International Brigade’ to save Czechoslovakia from the socialist system re-established as a result of the fraternal assistance operation.

The YCL has, inevitably, now almost collapsed, even its paper membership running only to a few hundreds. At its most recent congress it formally abandoned Marxism-Leninism and democratic centralism – thus moving decisively ‘ahead’ of the party congress fixed for this November.

From 1965 to 1977 the main characteristic of the inner-party struggles was the clash between the forces of the left and those of the leadership. The main fight now is within the leadership itself.

The majority centrists are being challenged by the growing forces of the right, forces which are proposing changes which go far beyond what anyone would have dreamed a mere matter of two years ago.

The inner struggle in the party lasted in distinct form for 12 years before the break was formalised, but the subsequent gallop to the right is not a mere result of that break and the consequent removal of the firmest of forces.

The attacks on the Soviet Union and other socialist countries and the process of changing the CPGB into an openly social-democratic organisation arise from far deeper causes than the positions of mere individuals, however outstanding and committed.

The roots of the process lie in the continued strength of reformism among the British working class, a strength based on Britain’s continued powerful imperialist position.

Opportunism is not a force which has to be created but a force which will gain strength wherever vigilance against it is relaxed.

The process having commenced in the CPGB, the ‘centre of gravity’ in the party inevitably tilted towards middle strata elements and the number of those elements and their importance was caused to grow yet more.

Despite all the evidence, despite all the political proofs, there remain some in the CPGB who say they agree with the political position of the New Communist Party but add that it is always wrong to split.

This view shows a mechanical approach to politics. Just because the CPGB had a fine tradition – exemplified by such communists as [Rajani Palme] Dutt and [Harry] Pollitt – does not negate the fact that these traditions are now being discarded as quickly as possible.

Splits are not wrong in themselves. It depends on the nature of the split.

The formation of communist parties in both France and Italy was only possible as a result of splits. The formation of the Bolshevik party itself only became possible as a result of a split. The Third International represented a complete split on a world basis between revisionism and the revolutionary parties…

… For us, the futile attempt to change the rotting corpse of the CPGB is a diversion. The real struggle lies far from that dead body, in the living world of class struggle, of the battle to overthrow the Tories and of the battle to achieve socialism.

Lenin broke with revisionism not over hair-splitting details but over the necessity to construct a revolutionary party capable of leading a successful revolution, none of which could have been done without a split.

The voices raised so loudly just two years ago against the decision to split are now notably muted, hushed by the unarguable fact that the CPGB shows not the remotest prospect of positive change. As for those who said the New Worker would last only a few weeks, their answer can be seen coming off the presses every Thursday of the year.

There were even people who said that the NCP would prove irrelevant to the working-class movement.

In fact, our role in combatting anti-Sovietism, in exposing the lies about the Ethiopian revolution, in the fight for peace, in supporting the heroic people of Vietnam in their resistance to Maoist invasion, in projecting a principled stand over the ‘Euro-elections’ and in a host of other matters – bread-and-butter working-class issues included – speaks for itself.

A party based on Marxism-Leninism and proletarian internationalism, we are not afraid to state, will never be irrelevant to the working-class movement of any country.

The world communist movement also gets mentioned in debate over our party.

Some sincere internationalists express concern because we do not as yet have fraternal relations with parties – particularly the CPSU – which have achieved state power for the working class. These sincere people are joined by a rather larger band of who cloak their opportunism and political bankruptcy in ‘internationalist’ robes.

From whichever group the argument originates it is both wrong and dangerous. Communist parties do not have the right to interfere in the internal affairs of other parties.

If this were not so, then, presumably, we would have to believe that the Soviet party’s silence indicates that it agrees with the positions of Dave Cook! The fact that the CPSU does not denounce every speech by [opportunist Spanish communist leader] Santiago Carrillo would have to be accepted as evidence that they agree [with] his views!

Extending the argument, we would have to accept the absurd view that splits in parties such as those of Greece, Australia and Sweden should not have taken place except with a guarantee that recognition would be immediately withdrawn from the revisionists and granted to the new party.

The sobering fact is that recognition is a privilege which must be earned, earned as the result of consistent struggle. To base political decisions on whether recognition is immediately forthcoming is not a Marxist view but the stuff of political cowardice.

Our party has already gained a great deal of international respect for the work it has conducted. Our efforts on such issues as those of peace, Ethiopia, Vietnam, Turkey, anti-Sovietism and solidarity with Czechoslovak socialism have meant that we are certainly not short of friends abroad.

We have no intention whatsoever of demanding recognition from anybody merely so as to encourage the faint-hearted. We will win international recognition through struggle.

The New Communist Party is still very small and beset by problems apart from those created simply by its size. It has to face constant attack from both the overall capitalist ideological offensive mounted through the mass media and from the forces of revisionism and opportunism within the British working-class movement.

This two-pronged attack has had its effects on our party but the struggle to resist has led to a strengthening of our resolve to build the party, to transform it into the true vanguard of the British working class.

For us there can be no question of retreat, no question of following the path of conciliation…

We call upon all genuine communists, all class-conscious workers, whether in the CPGB or not, to join us in the fight. Britain has only one party based on Marxism-Leninism and proletarian internationalism and that party is the NCP.

Those who believe themselves to be revolutionaries must now decide which path they are going to follow. The choice is between the path of struggle and the path which leads straight to the marsh.