Writing on factional battles in the old Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) in the 1980s, Mark Fischer, active in The Leninist of that era, observed: “… the revolutionary left outside the party took an extremely passive, intensely insular and – initially – factually inaccurate view when large-scale factional war in the CPGB broke out openly in the 1980s. If I were feeling charitable, I might say that this was at least partially explained by the troglodyte existence of the oppositional trends – with the exception of The Leninist, of course. However, I think the real reason was the crude caricature of the CPGB and its internal life that most had lumbered themselves with.”[i]

Such caricatures fed off a schema regarding how such groups pictured their future. Fischer added: “The demise of the CPGB was celebrated by many of the revolutionary sects, as they held that, with the party out of the way, the time had come for their group at last. In the 1990s generally, a similarly sanguine view was common: the death of the ‘official’ world communist movement was not an ideological victory for imperialism, but, rather, their particular brand of Trotskyism…”[ii] An achingly beautiful illustration of such idiocy can be found from Ian Birchall in 1985, then writing for the British Socialist Workers Party (SWP): “In itself the demise of the CPGB will bring no profit to the revolutionary left; but at least a confusing diversion has been removed from the political scene. At the end of Balzac’s novel Old Goriot the ambitious young Rastignac gazes down at the vast city of Paris and pledges: ‘It’s between the two of us now!’ With the CP out of the way, the SWP can address the Labour Party in similar terms.”[iii] Now, this dozy hubris was the cause of much mirth in 1985, let alone in 2022, but it does illustrate that the SWP and others thought about the old CPGB in much the same way as boy racers think about OAP drivers (i.e. get out of the way).

Rival paper-sellers

The SWP therefore had no real insight to offer about the CPGB in the 1980s; it knew little about the party’s left factions (more rival paper-sellers as far as the SWP was concerned); overused the term ‘Stalinist’ in a pejorative manner that explained very little; and while I wouldn’t accuse the SWP of being Eurocommunist, it wrote in occasional diplomatic terms about Marxism Today and the Euro faction (the Euros, were, like the SWP, extremely hostile to the Labour left, and the entryist Militant was a much more successful organisation than the SWP in this period).

This ‘us-next’, ‘collapse of communism’ mentality quickly evaporated, and, in fact, political groups associated with the legacy of ‘official’ communism, Maoism and JV Stalin survived and have recently shown signs of relative prosperity. In that situation, one would perhaps expect the inaccuracies and impatience of the 1980s to drop away in favour of cold-headed realism among those in the Trotskyist (and perhaps post-Trotskyist) milieu given that it patently hasn’t been their ‘turn’ and the idea of addressing the Labour Party on even the grossly unequal terms that the CPGB once did has been exposed as a lurid fantasy.

One of the fragments of the British SWP is around a journal called Salvage. Barnaby Raine has written an article that deals with the return of what he calls ‘campism’ i.e. an attachment to ‘really existing’ communism, past and present, its leaders and other accoutrements. For Raine, that is a form of ‘Left Fukuyamaism’, a political pessimism that bears “witness to the awkwardness that accompanies talk of hope and freedom and equality today”.[iv] ‘Salvage’ is an interesting word in this context in that Raine’s article, while offering what appears to be a critique of ‘campism’, in fact involves a conservative salvage operation of the SWP’s sectarian hostility to the CPGB and its left factions. Thus, sectarian taxonomies are revived, and all the old crap of the 20th century reappears in new clothes.

‘Young things in black leather jackets’

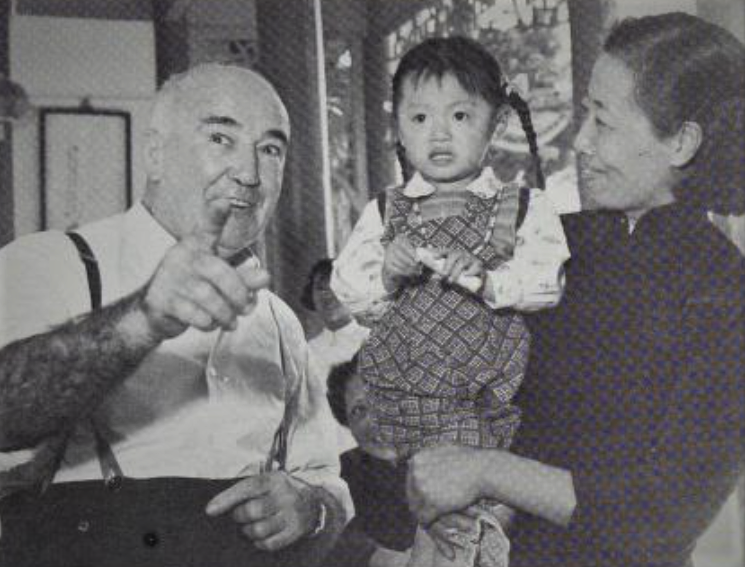

You can find on YouTube a 1991 Channel 4 documentary called The end of the party, some of which documents a CPGB-PCC/The Leninist picket of the ‘official’ CPGB’s liquidation congress (pictured above).[v] Raine recounts these scenes: “[CPGB veteran Rose Kerrigan] walks past a small band of young things in black leather jackets. ‘No matter how you change your name’, they shout into the hall, ‘you still play the bosses’ game!’ These are the savvy twins to the Eurocommunist reformers, the young Stalinists who know which way the wind is blowing. They’ve left the party, and they call it a corpse. Their newspaper is The Leninist, and against the stream they champion (albeit critically) the Russian tanks that once rolled into Budapest and Prague. Theirs is no mass party. They are the enlightened few. To them, as to the Eurocommunists, Rose who will not give up her old party is an old fool.”[vi]

This passage relies on an old Trotskyist/SWP canard: that the internal factional battles of the CPGB’s last decades were about ‘tankies versus Euros’; symbiotic twins underpinned by the master label ‘Stalinist’. Therefore, the CPGB could be dismissed in toto as an obstruction and barrier to the SWP et al. There were a variety of factions in the CPGB and, on its left, those factions had tended to use either Mao’s China or the Soviet Union as a symbol of communist virility, allied to a revolutionary critique of the CPGB’s reformist strategy. Such groups were thus a unity of opposites and later factions such as The Leninist studied Lenin and Trotsky to understand the CPGB’s history and elaborate a critique of the world communist movement. But, of course, such groups reflected to some degree their emergence inside the CPGB (i.e. on issues such as Hungary 1956 and Czechoslovakia 1968); they weren’t perfect in the same way that Salvage couldn’t possibly emerge as a perfectly rounded enterprise, pockmarked as it was by the experience of the SWP.

Raine accurately recounts what the CPGB-PCC picket shouted at the congress: ‘No matter how you change your name, you still play the bosses’ game!’ This shows that these supposed “young Stalinists” had a sense of their history, in that the CPGB was still playing the bosses game, a recognition of the party’s reformist role under the likes of Stalin (The Leninist, in fact, used the pre-Stalin CPGB of the 1920s as an inspiration). As I said recently on this blog, genuine “young Stalinists” are much more cautious in relation to the party’s history and haven’t yet shouted anything quite like that.

The rest of Raine’s passage, judged by historical evidence easily available these days, is composed of similar nonsense. The CPGB-PCC did not leave the ‘official’ CPGB and call it a corpse. Some of its members were expelled but it argued that comrades still had duties to the party, in this instance, to reforge the CPGB, of which it saw itself as a faction and not the party. Raine says: “Theirs is no mass party. They are the enlightened few.” In that case, why then did the group announce its provisional status (then as now) and call activists back to the party to help reforge it? The tragedy of the CPGB-PCC is that this part of its enterprise failed, and it has been left with the title ‘CPGB’ and little else. But it is clear from The Leninist of the period that its future existence was not planned as an elect body of the “enlightened few”.

Raine adds: “To [the CPGB-PCC], as to the Eurocommunists, Rose who will not give up her old party is an old fool.” Again, nowhere will you find articles in The Leninist of the time urging older CPGB members to simply give up on the party. I don’t think Raine should get too carried away with the sight of all those young people in black jackets. The Leninist had a few activists that had been members of the Young Communist League since the 1960s and, as the 1980s went on, a small number of older CPGB veterans (Ted Rowlands, Tom May, Reg Weston etc.) contributed to the group; Jack Dash and Vic Turner were involved in campaigns such as the Unemployed Workers’ Charter and Turner became a CPGB-PCC supporter in the mid-1990s for a short period when he was a sitting Labour Party councillor.[vii] It would be a mistake to over-emphasise this and The Leninist was still primarily composed in 1991, as The end of the party shows, of kids. (The majority of the veterans went to the much-larger Morning Star/Communist of Party of Britain, which split from the ‘official’ CPGB in 1988.) But The Leninist or the CPGB-PCC never showed the loutish and defeatist attitude to party veterans that Raine alleges.

Ramelson the ‘tankie’?

Other parts of Raine’s article show an ignorance of the history of the CPGB: “In Britain, whose Communist Party was never a national electoral force but held serious industrial significance, ‘tankieism’ means memories of brilliant and effective organisers like Bert Ramelson and Derek Robinson: ‘Red Robbo’, who terrified the press.”[viii] This clumsy epithet ‘tankie’ seems to have appeared, according to veteran journalist Sam Russell (interviewed by Beatrix Campbell in a 1989 Arena documentary for the BBC on the history of the Daily Worker), in internal arguments after the Soviet Union’s 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia. One editorial member of the Daily Worker team was remembered to have said, in response to criticisms of the Soviet action, that he “would sleep far better at night if there were Soviet tanks in Farringdon Road”.[ix] It seems that this positive appreciation of Soviet tanks was then worked over into a negative term of abuse, whose later history has been partly traced by Evan Smith.[x]

But this has precious little to do with Bert Ramelson because it was Ramelson who took the call from the Soviet embassy telling the CPGB what had occurred in Czechoslovakia. As recounted by Reuben Falber: “In the heated exchange which followed, Bert challenged the truth of the claim that the Czechoslovak Party leadership had invited the Warsaw Pact troops in and warned that the British Communist Party would not accept so blatant an intrusion into the affairs of a fraternal party and another socialist country.”[xi] At the 1969 CPGB congress, it was Ramelson who answered the pro-Soviet arguments of the veteran Rajani Palme Dutt, who supported the Soviet invasion.[xii] So, whatever Bert Ramelson was, he wasn’t a ‘tankie’ but in a sense that doesn’t matter for Raine because he has elastic and pejorative terminology (‘Stalinist’, tankie’ etc.) that can simply explain all kinds of heterogenous people and things in the old CPGB without reference to its actual history. As with Raine’s material on The Leninist, some very simple research would have led him away from such howlers.

Whatever the motivations of Raine himself, the roots of such literary practice lie in the impatient and snide mythology of the SWP that itself contains a pessimism in favour of the perpetuation of its own sect existence. So, if Raine says that recent relative enthusiasm for Stalin and the Soviet Union is evidence of pessimism inside the workers’ movement then he has only arrived at a tautology given that such a view was already inherent in the insensitive categories so clearly inherited from the SWP. In fact, the historical trajectory of the left versions of pro-Sovietism (and pro-Maoism) that emerged in the CPGB were also shot through with an optimism in relation to the critique of the politics of ‘official’ communism in Britain, and an idea that they could be reforged anew. Unless you face that startling contradiction then you will understand little of the so-called ‘new Stalinism’, which itself is partly lodged in a critique of existing organisations and leaders; and partly in an unedifying reification of the past.

[i] https://weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/940/cpgb-history-illuminating-the-factional-struggles-/

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/birchall/1985/xx/cpgb.html

[iv] https://salvage.zone/left-fukuyamaism-politics-in-tragic-times/

[v] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zbZeqwFxaQw The CPGB-PCC picket appears after 7.00.

[vi] https://salvage.zone/left-fukuyamaism-politics-in-tragic-times/

[vii] https://weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/89/defending-the-pretence-of-socialism/

[viii] https://salvage.zone/left-fukuyamaism-politics-in-tragic-times/

[ix] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gq_LQYOb90M 50.48.

[x] https://hatfulofhistory.wordpress.com/2020/01/27/tankie-the-origins-of-an-epithet/

[xi] Cited in R Seifert and T Sibley Revolutionary communist at work: a political biography of Bert Ramelson London 2012 p161.

[xii] Ibid p162.